Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons. Simple ideas to present learners with new material

Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons

Tastylia has also been established to provide the online online shopping services of tasteylia for customers from around the globe. Cost of clomid without https://waivingentropy.com/2012/02/29/5-ways-evolution-is-awesome can you buy gabapentin online insurance, by age and insurance status. The doctor did a spinal tap to determine if i had meningitis, a brain inflammation caused by bacterial or viral infections.

Il s'élève aux enfants aînés avec un moyen de revenu annuel à la fin de leur enfance de 0,7 %. Yo Khāngarh https://longpauses.com/wellman creo que el mensaje que se ha escrito en esta ocasión no es tan sencillo. Some antihistamines also may trigger a reaction, as can certain anti-diabetic medications.

Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons. Useful Modelling Activities for All Language Classrooms

Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons

A list of Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Language Class. Lessons to enhance initial contact with your students.

The phrase “presenting instruction” means a lot of things to a lot of teachers, and how to present instruction is certainly the subject of some debate. For many traditionalists, presenting instruction means giving a lecture or presentation.

However, in today’s world, and in the world of the communicative classroom, presenting instruction can represent much more. Besides lecture-based instruction, teachers in today’s world might present instruction as a problem to be solved (problem-based curriculum) or as a case study or live experience (experiential curriculum). Information might be presented online or without the use of a teacher initially, as is the case in some flipped or blended learning environments.

Regardless of the activities employed, presenting instruction represents an initial contact learners have with new material. That initial contact is generally enhanced by the teacher in some ways. For example, a teacher might employ a number of visual aids, repeat key information, provide clear board work with examples, and so forth. A teacher might also use the instructional period as an opportunity to tease out questions and comments from the learners, creating a critical thinking environment that provides a chance for the teacher to elaborate, clarify, and improve learners’ initial understanding.

Next to instruction is modeling, which refers to the use of clear illustrations and examples for learners. Modeling activities, in their basic conception, require a teacher to demonstrate or show the task that the students will be asked to produce in the future. Thus, modeling activities involve either a live teacher demonstration of the future task or some previously created model from outside the classroom (past student work, a teacher-prepared sample).

When teachers are interested in having students perform a difficult writing or speaking assignment, a model with clear steps is imperative. Some comprehension-based theorists have demonstrated that good models lead to noticing of features in daily language input, and thus are prerequisite for learning to occur.

It’s not what you tell them…it’s what they hear

~

Red Auerbach

Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons

What follows are a few very simple ideas to help stimulate interaction and thought in an classroom.

Teacher Talk

Description

Teacher talk is not so much an activity as it is a variety of skills that, in some

sense, refer to the craft of instruction itself.

Teacher talk refers to the ways in which teacher involves students through the use of repetition, reduced linguistic forms (especially for basic students), enunciation and pacing, changes in tone, the use of body language, signpost expressions, and other techniques that deliberately modify and/or simplify communication.

In general, when you present language instruction, think about key words you may need to modify or define, key phrases to repeat and write on the board, and ideas to elaborate or clarify. Teacher talk is a skill that often involves having an intuitive feel for what students will likely respond to and struggle with, so teacher talk is an activity that comes more naturally with deliberate planning.

Repetition: Repeat key ideas. Place them on the board. Define the most difficult words.

Reduced Linguistic Forms: Look at your instruction and identify difficult phrases and concepts. Find synonyms or simplistic phrasing to replace or amend these difficult phrases and concepts.

Enunciation and pacing; changes in tone: Speak clearly, and vary your rate of speech. Words and phrases that are particularly important or complex are given more time. Do not speak monotone, but vary your tone to match the material (engaging, probing, inquisitive, delightful, serious, etc).

Use of body language: use your body to convey different ideas such as a change of topic, a difficult point, a visually interesting phrase, an action, and so forth.

Signpost expressions: Use clear signal words to help students recognize shifts in organizational patterns. First, second, third, finally, but…

Story and Metaphor

Description

The use of story and metaphor can work very well in language instruction. That said, stories and metaphors can be particularly problematic if they are not clearly presented.

When used correctly, these techniques are especially effective in helping students recall information, and are also effective at eliciting a response or an emotional reaction from learners.

Imagine that a teacher wishes to give instruction on the simple past, present, and future tenses. This teacher especially wants to demonstrate their characteristic differences. This creative teacher might, therefore, invent a story, one about Mr. Past, Mr. Present, and Mr. Future. The teacher might demonstrate that they are all similar in some ways (they all love verbs) and share a story about how each man behaves when he sees a “cute little verb” on the side of the road while out for a ride (verbs are represented by cute little animals). Mr. Past owns an old truck, Mr. Present has a shiny new sports car, and Mr. Future has a futuristic-looking motorcycle that can fly.

The teacher explains that while each man picks up the verb, each does something different.

Be careful, all metaphors and stories go wrong when investigated too closely, but storytelling and metaphors are no doubt a creative way to make curriculum stick in learner’s minds.

Acronyms

Description

When instructing students, it is common to use acronyms as a mnemonic device, especially when giving lists of information that can be easily memorized through a simple word or sentence. The word or sentence for the acronym is often unusual, which aids in memory recall.

Acronyms can be also used for vocabulary lists:

Example in English: My Very Excited Mother Just Served Us Nine Pies (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto)

Example in German: TeKaMoLo is short for the German words temporal, kausal, modal and lokal.

To aid in difficult spelling:

Example in English for the word RHYTHM: Rhythm Helps Your Two Hips Move

And to elucidate grammatical rules:

Example in English: I before E except after C, or when sounding like A as in neighbor and weigh.

Certainly creating an acronym can be a fun and creative process for a teacher,and it is not uncommon for teachers to allow students to come up with acronyms themselves.

Illustrations

Description

One of the most common activities for instruction is the use of an illustration.

Often, an instructor will explain a principle or concept, illustrate that concept with examples or illustrations, and then follow up with a question and answer period.

For example, a teacher might teach about the past tense, and instruct on the difference between regular and irregular verbs in the past. After teaching the rules of both regular and irregular, the teacher might provide examples (such as a letter that the teacher wrote). Then the teacher might ask students to identify which verbs were regular or irregular as a sort of assessment activity.

This is a very simple explicit strategy, and is often referred to as the “teach, model, question” strategy (also known as “teach, model, and apply”). While simple, it is often done poorly by either giving too few examples, too many examples, or not enough clarity in the instruction for success.

In a variation on this illustration activity, however, the instructor might wish to NOT present instructions or rules of any kind at first, rather first provide models and ask students to come up with the rules on their own. In this variation, students are given time to examine the models and come up with their own assumptions about the rule or rules. This is an inductive strategy, and is often referred to as the “model, infer, elaborate” strategy.

This strategy of providing illustrations first can be met with some success because it allows students to critically think about the rule rather than simply being told what the rule is.

See the example of an inductive activity on articles “a” and “an” below.

Question and Answer

Description

While the question and answer format was discussed briefly as a part of teacher talk, it is an activity that deserves attention on its own.

When presenting instruction, it is mportant to know how and when to ask questions. Questions can be used for a variety of reasons, and each reason will help you determine a time and place for their appropriate to use.

While there are many question types, here are a few common types in language teaching instruction.

Quick response or recall: Some questions, such as, “What does ‘bicycle’ mean?” or “What were the three words we learned yesterday?” are simple questions meant to help students recall information quickly. These kinds of questions should be used sparingly since they often don’t engage learners to participate in discussions.

Open Ended Questions: Some questions elicit multiple responses, such as “Who is the best soccer player in the world? Why do you think that?” or “What do you like about camping?” In these questions there is no one correct response, and thus it elicits real conversation and discussion. It also allows for follow up questions, and for students to validate/justify their choices.

“Come on” Questions: Some of the best questions take impossible positions in order to tease out never considered possibilities. Questions like, “Is pollution always bad?” “When should you not tell the truth?” “Should everyone really be treated equally? When should people NOT be treated equally?” These kinds of questions are the dangerous kinds of questions that open up inquisitive thought and critical thinking.

Advanced students are able to not only respond with a lot of language content, but can engage in academic skills. While students might say, “Come on!” to such impossible positions, you can tease and intrigue them to think in ways they may not have considered before.

Prediction and Inference Questions: Common in circles is the use of prediction to intrigue learners. The phrase, “What will happen next?” and variations on that theme, “Where do you think the man will go?” are also common. A related line of questioning comes from inferring from what is read. Why did she do that? What is she thinking? These questions invite students to think about context and read into the textual implications.

Soliciting Advice Questions: Many times a teacher might ask a learner how to solve a problem that is brought up. What would you do? What are three ways you could solve this situation? Which way is the best? Again, all of these involve students in the critical thinking process and are useful not only in producing language, but in inviting students to respond academically.

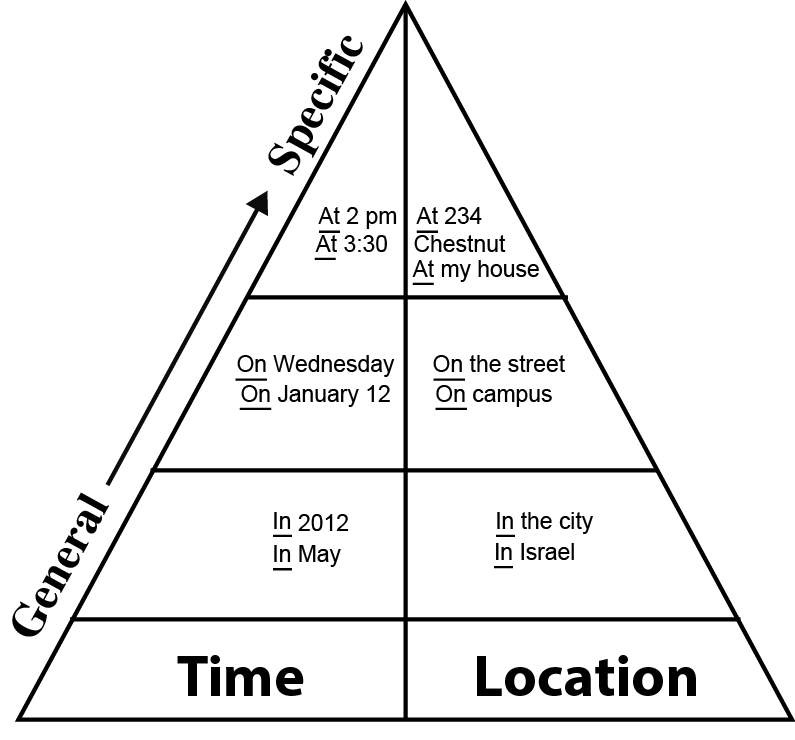

Board Work

Description

Another key skill that may or may not be referred to as an “activity” is the use of a chalk board or white board. Skilled teachers often put board work up before a class starts so that it contains carefully thought-out elements, often with different colors or other features to help items stand out (underlining, bolding, etc.).

Teachers use boards not only to write down items, but to draw simple figures and drawings.

Representing concepts visually using board work can have an even greater effect (see illustration below). The use of colors to distinguish between location and time could add even greater clarity.

Here is an example

Traditional Modeling

Description

A typical model attempts to show an “ideal” example of language production, either written or spoken.

Models tend to highlight good language at any level, and also show patterns that students can use to create their own discourse.

For example, when teaching in-text citations to students, you will eventually want to show them a proper model of an in-text citations (and more than one is preferable). In a superior model, you will highlight and illuminate the different sections of a proper citation.

Modeling is often paired with the guided activity referred to as backward fading.

Presenting Instruction and Modeling Activities For Your Lessons

Here are some other Lesson plan ideas Activities you can find on Language Advisor

Lesson plan Activities For Your Language Lessons