Beyond the Crowd: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Deconstructing the Bandwagon Fallacy. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Beyond the Crowd: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Deconstructing the Bandwagon Fallacy

Beyond the Crowd: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Deconstructing the Bandwagon Fallacy

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

The Bandwagon Fallacy

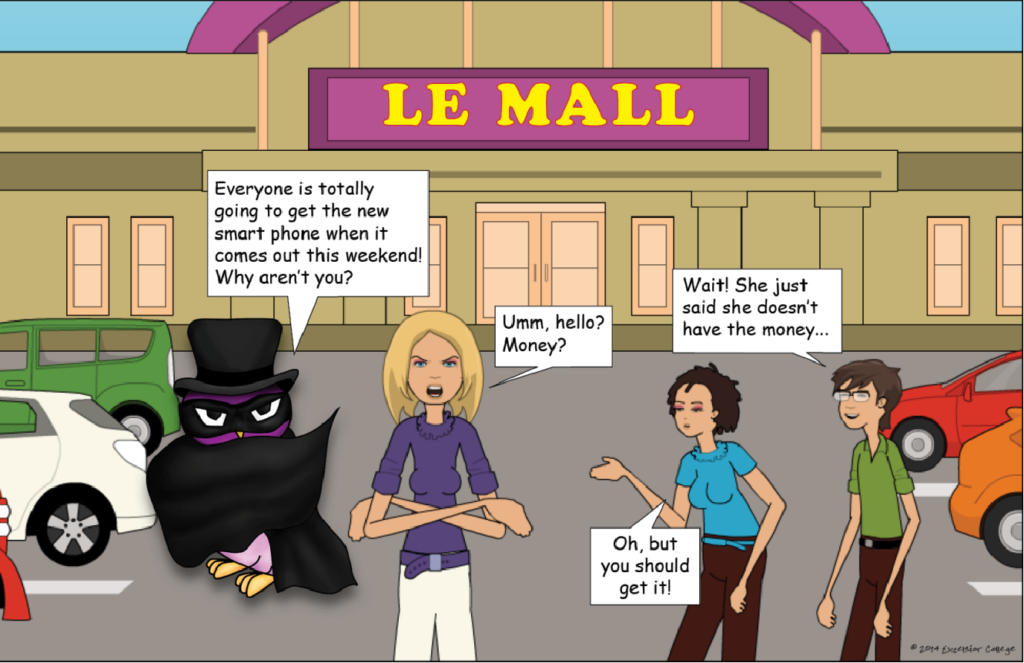

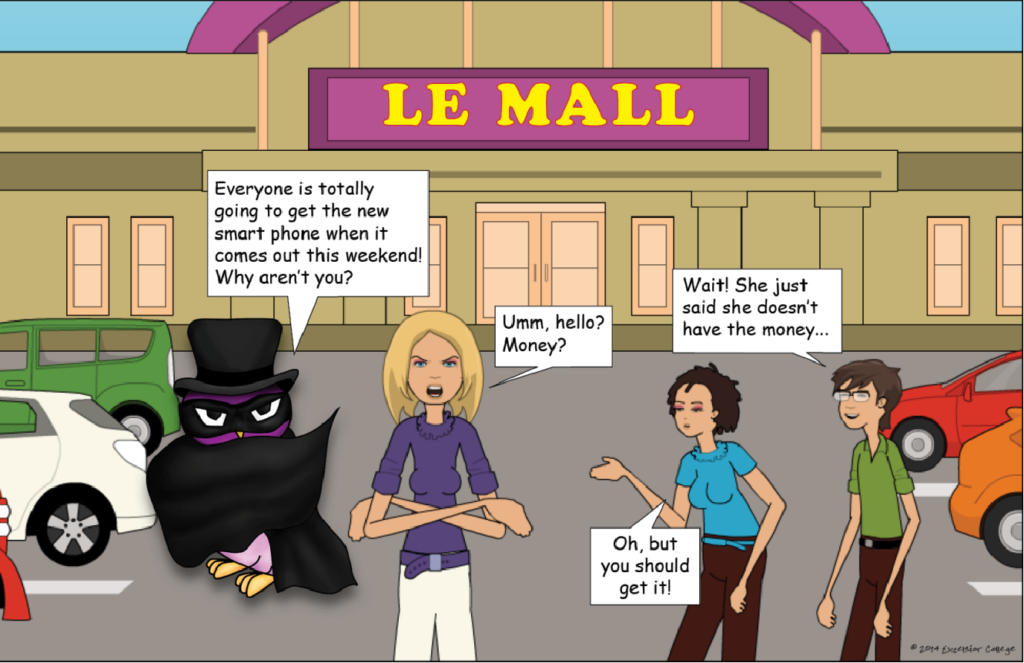

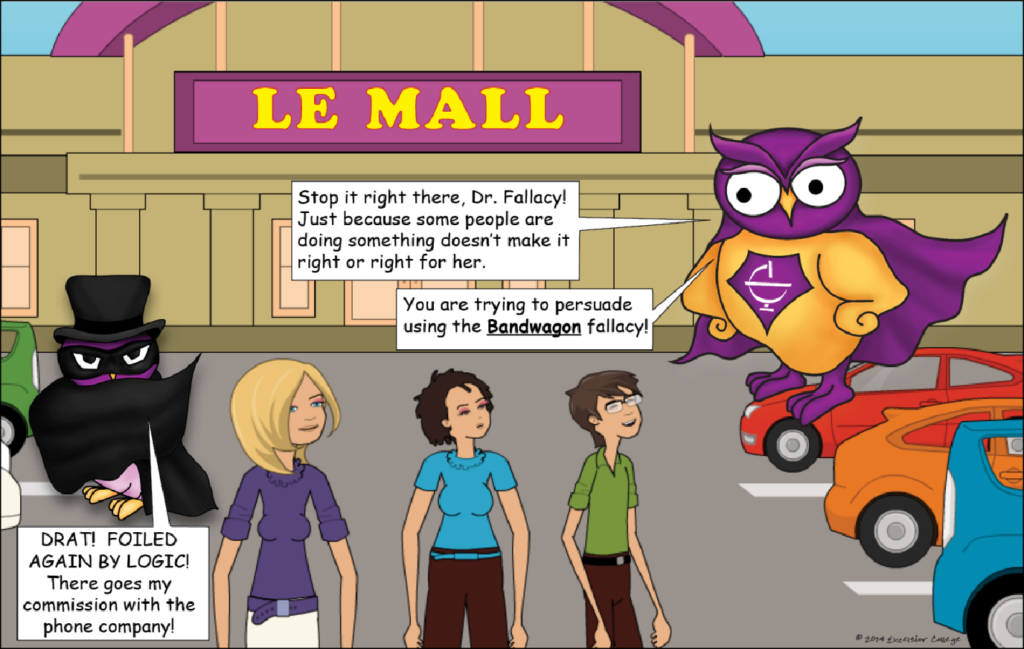

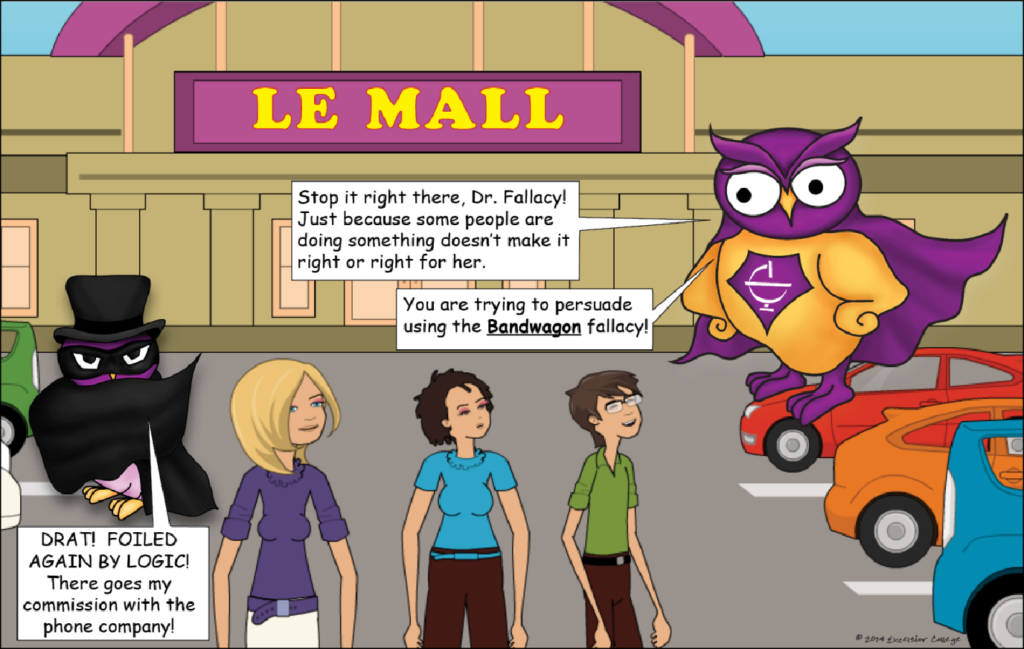

The bandwagon fallacy assumes something is true (or right, or good) because other people agree with it. A couple different fallacies can be included under this label, since they are often indistinguishable in practice. The ad populum fallacy (Lat., “to the populous/popularity”) is when something is accepted because it’s popular. The concensus gentium (Lat., “consensus of the people”) is when something is accepted because the relevant authorities or people all agree on it. The status appeal fallacy is when something is considered true, right, or good because it has the reputation of lending status, making you look “popular,” “important,” or “successful.”

For our purposes, we’ll treat all of these fallacies together as the bandwagon fallacy. According to legend, politicians would parade through the streets of their district trying to draw a crowd and gain attention so people would vote for them. Whoever supported that candidate was invited to literally jump on board the bandwagon. Hence the nickname “bandwagon fallacy.”

This tactic is common among advertisers. “If you want to be like Mike (Jordan), you’d better eat your Wheaties.” “Drink Gatorade because that’s what all the professional athletes do to stay hydrated.” “McDonald’s has served over 99 billion, so you should let them serve you too.” The form of this argument often looks like this: “Many people do or think X, so you ought to do or think X too.”

One problem with this kind of reasoning is that the broad acceptance of some claim or action is not always a good indication that the acceptance is justified. People can be mistaken, confused, deceived, or even willfully irrational. And when people act together, sometimes they become even more foolish — i.e., “mob mentality.” People can be quite gullible, and this fact doesn’t suddenly change when applied to large groups.

Beyond the Crowd: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Deconstructing the Bandwagon Fallacy

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies