Hasty Conclusions: Navigating Logical Fallacies and Unraveling the Pitfalls of Hasty Generalization. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Hasty Conclusions: Navigating Logical Fallacies and Unraveling the Pitfalls of Hasty Generalization

Hasty Conclusions: Navigating Logical Fallacies and Unraveling the Pitfalls of Hasty Generalization

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

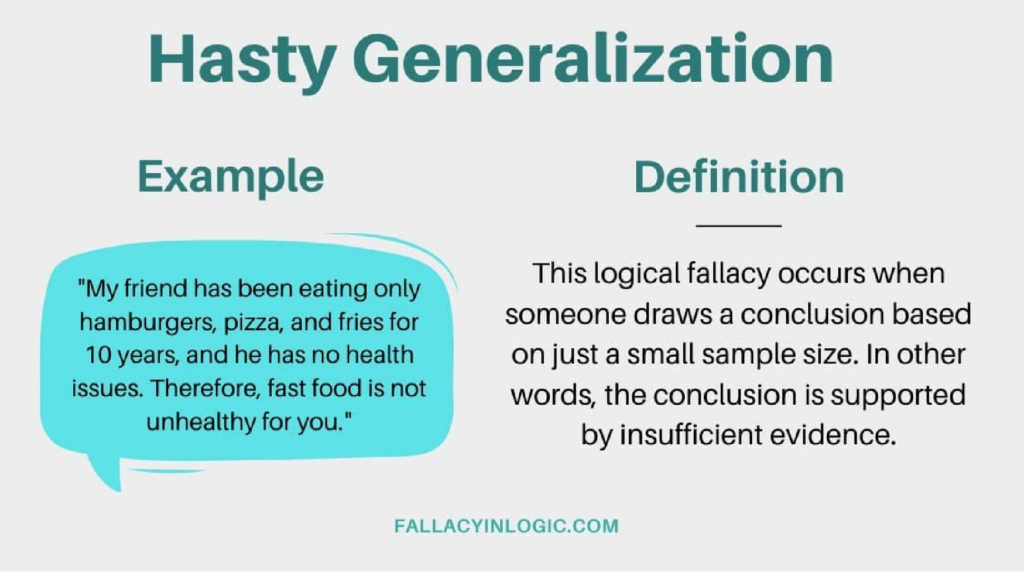

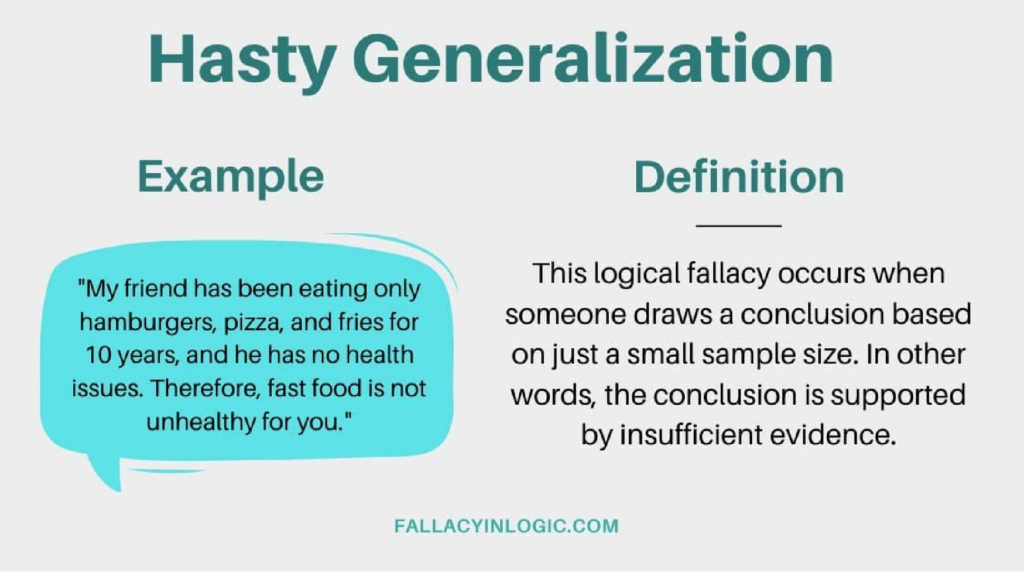

The Hasty Generalization

A hasty generalization is a general statement without sufficient evidence to support it. A hasty generalization is made out of a rush to have a conclusion, leading the arguer to commit some sort of illicit assumption, stereotyping, unwarranted conclusion, overstatement, or exaggeration.

Normally we generalize without any problem; it is a necessary, regular part of language. We make general statements all the time: “I like going to the park,” “Democrats disagree with Republicans,” “It’s faster to drive to work than to walk,” or “Everyone mourned the loss of Harambe, the Gorilla.”

Hasty generalization may be the most common logical fallacy because there’s no single agreed-upon measure for “sufficient” evidence.

Indeed, the above phrase “all the time” is a generalization — we aren’t literally making these statements all the time. We take breaks to do other things like eat, sleep, and inhale. These general statements aren’t addressing every case every time. They are speaking generally, and, generally speaking, they are true. Sometimes you don’t enjoy going to the park. Sometimes Democrats and Republicans agree. Sometimes driving to work can be slower than walking if the roads are all shut down for a Harambe procession.

Hasty generalization may be the most common logical fallacy because there’s no single agreed-upon measure for “sufficient” evidence. Is one example enough to prove the claim that, “Apple computers are the most expensive computer brand?” What about 12 examples? What about if 37 out of 50 apple computers were more expensive than comparable models from other brands?

There’s no set rule for what constitutes “enough” evidence. In this case, it might be possible to find reasonable comparison and prove that claim is true or false. But in other cases, there’s no clear way to support the claim without resorting to guesswork. The means of measuring evidence can change according to the kind of claim you are making, whether it’s in philosophy, or in the sciences, or in a political debate, or in discussing house rules for using the kitchen. A much safer claim is that “Apple computers are more expensive than many other computer brands.”

Meanwhile, we do well to avoid treating general statements like they are anything more than simple, standard generalizations, instead of true across the board. Even if it is true that many Apple computers are more expensive than other computers, there are plenty of cases in which Apple computers are more affordable than other computers. This is implied in the above generalization, but glossed over in the first hasty generalization.

A simple way to avoid hasty generalizations is to add qualifiers like “sometimes,” “maybe,” “often,” or “it seems to be the case that . . . “. When we don’t guard against hasty generalization, we risk stereotyping, sexism, racism, or simple incorrectness. But with the right qualifiers, we can often make a hasty generalization into a responsible and credible claim.

Hasty Conclusions: Navigating Logical Fallacies and Unraveling the Pitfalls of Hasty Generalization

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies