Circling Logic: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Exposing the Circular Reasoning Fallacy. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Circling Logic: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Exposing the Circular Reasoning Fallacy

Circling Logic: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Exposing the Circular Reasoning Fallacy

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

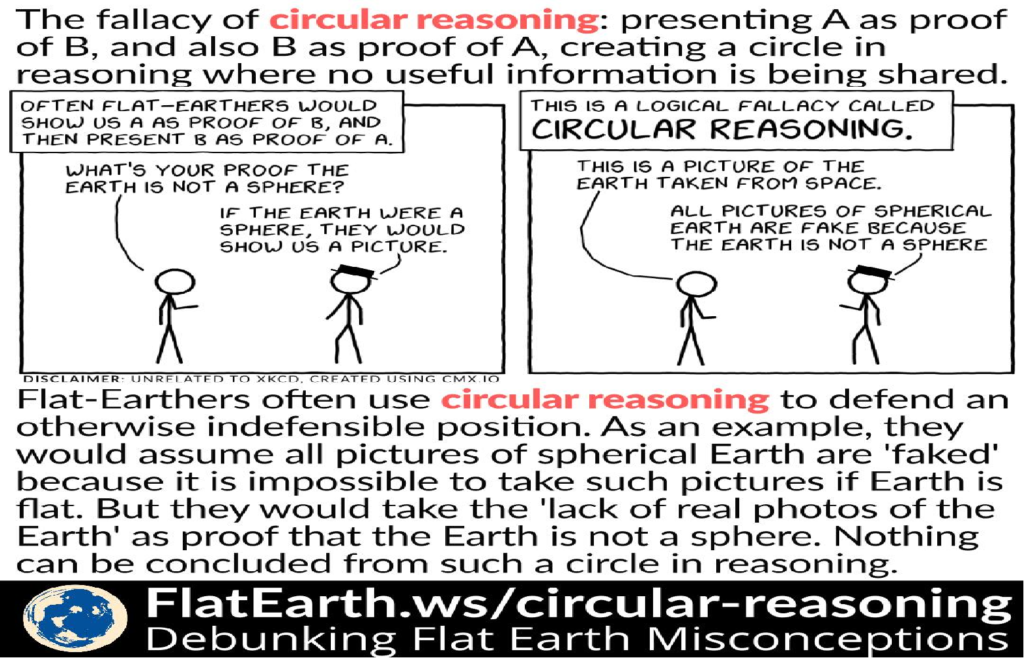

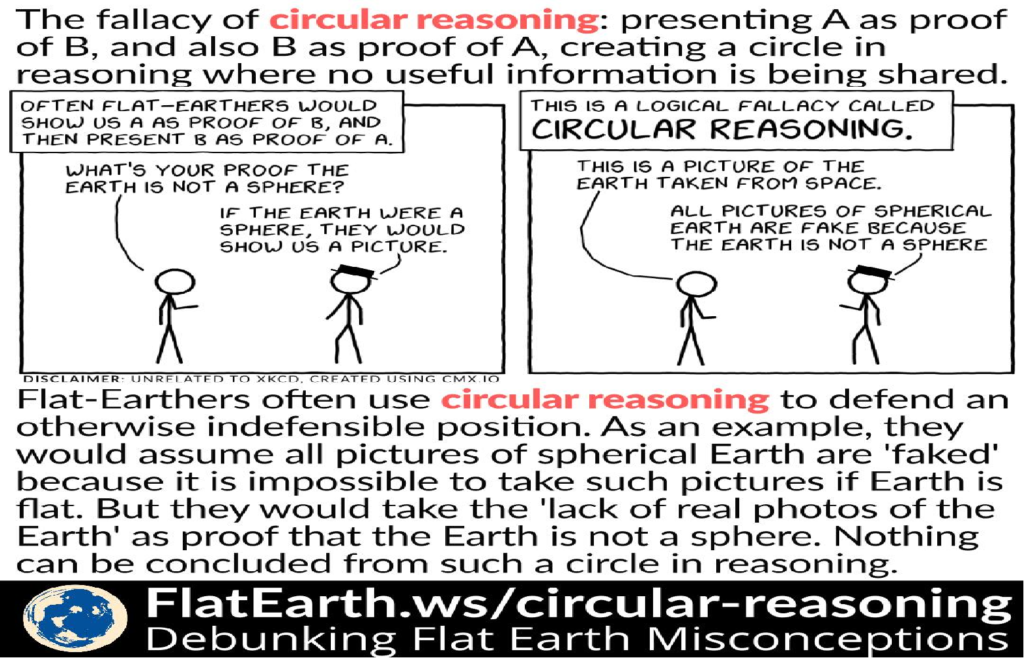

The Circular Reasoning Fallacy

When a person’s argument is just repeating what they already assumed beforehand, it’s not arriving at any new conclusion. We call this a circular argument or circular reasoning. If someone says, “The Bible is true; it says so in the Bible”—that’s a circular argument. They are assuming that the Bible only speaks truth, and so they trust it to truthfully report that it speaks the truth, because it says that it does. It is a claim using its own conclusion as its premise, and vice versa, in the form of “If A is true because B is true; B is true because A is true”. Another example of circular reasoning is, “According to my brain, my brain is reliable.” Well, yes, of course we would think our brains are in fact reliable if our brains are the one’s telling us that our brains are reliable.

Circular arguments are also called Petitio principii, meaning “Assuming the initial [thing]” (commonly mistranslated as “begging the question”). This fallacy is a kind of presumptuous argument where it only appears to be an argument. It’s really just restating one’s assumptions in a way that looks like an argument. You can recognize a circular argument when the conclusion also appears as one of the premises in the argument.

Circling Logic: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Exposing the Circular Reasoning Fallacy

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies