Cause and Confusion: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Investigating the Causal Fallacy. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Cause and Confusion: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Investigating the Causal Fallacy

Cause and Confusion: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Investigating the Causal Fallacy

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

The Causal Fallacy

The causal fallacy is any logical breakdown when identifying a cause. You can think of the causal fallacy as a parent category for several different fallacies about unproven causes.

One causal fallacy is the false cause or non causa pro causa (“not the-cause for a cause”) fallacy, which is when you conclude about a cause without enough evidence to do so. Consider, for example, “Since your parents named you ‘Harvest,’ they must be farmers.” It’s possible that the parents are farmers, but that name alone is not enough evidence to draw that conclusion. That name doesn’t tell us much of anything about the parents. This claim commits the false cause fallacy.

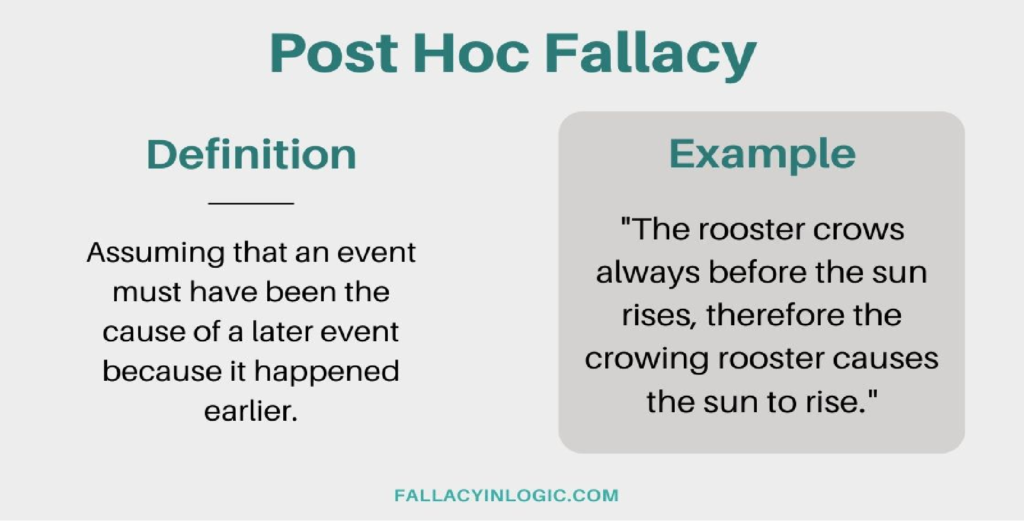

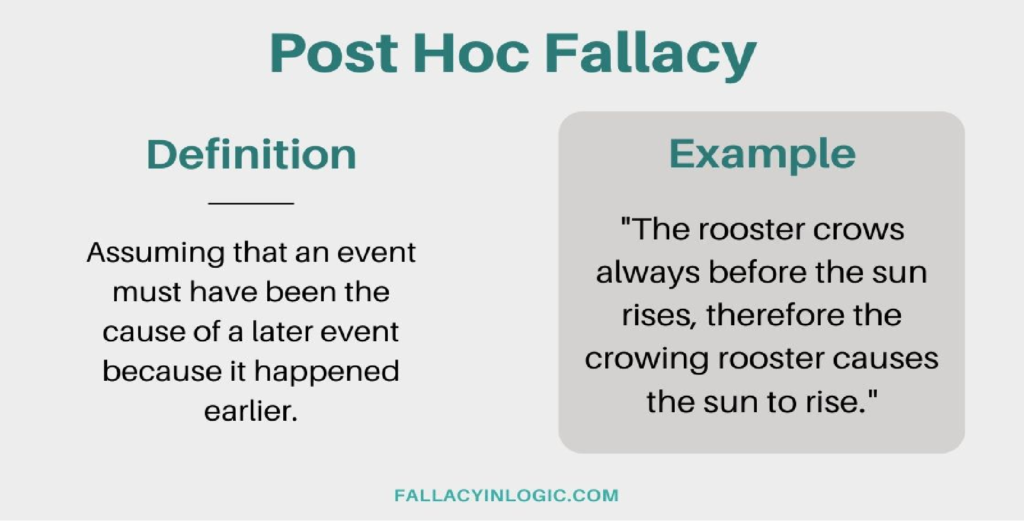

Another causal fallacy is the post hoc fallacy. Post hoc is short for post hoc ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”). This fallacy happens when you mistake something for the cause just because it came first. The key words here are “post” and “propter” meaning “after” and “because of.” Just because this came before that doesn’t mean this caused that. Post doesn’t prove propter. A lot of superstitions are susceptible to this fallacy. For example:

“Yesterday, I walked under a ladder with an open umbrella indoors while spilling salt in front of a black cat. And I forgot to knock on wood with my lucky dice. That must be why I’m having such a bad day today. It’s bad luck.”

Now, it’s theoretically possible that those things cause bad luck. But since those superstitions have no known or demonstrated causal power, and “luck” isn’t exactly the most scientifically reliable category, it’s more reasonable to assume that those events, by themselves, didn’t cause bad luck. Perhaps that person’s “bad luck” is just their own interpretation because they were expecting to have bad luck. They might be having a genuinely bad day, but we cannot assume some non-natural relation between those events caused today to go bad. That’s a Post Hoc fallacy. Now, if you fell off a ladder onto an angry black cat and got tangled in an umbrella, that will guarantee you one bad day.

Another kind of causal fallacy is the correlational fallacy also known as cum hoc ergo propter hoc (Lat., “with this therefore because of this”). This fallacy happens when you mistakenly interpret two things found together as being causally related. Two things may correlate without a causal relation, or they may have some third factor causing both of them to occur. Or perhaps both things just, coincidentally, happened together. Correlation doesn’t prove causation.

Consider for example, “Every time Joe goes swimming he is wearing his Speedos. Something about wearing that Speedo must make him want to go swimming.” That statement is a correlational fallacy. Sure it’s theoretically possible that he spontaneously sports his euro-style swim trunks, with no thought of where that may lead, and surprisingly he’s now motivated to dive and swim in cold, wet nature. That’s possible. But it makes more sense that he put on his trunks because he already planned to go swimming.

Cause and Confusion: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Investigating the Causal Fallacy

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies