Hypocrisy Unveiled: Exploring Logical Fallacies and Navigating the Appeal to Hypocrisy. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Hypocrisy Unveiled: Exploring Logical Fallacies and Navigating the Appeal to Hypocrisy

Hypocrisy Unveiled: Exploring Logical Fallacies and Navigating the Appeal to Hypocrisy

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

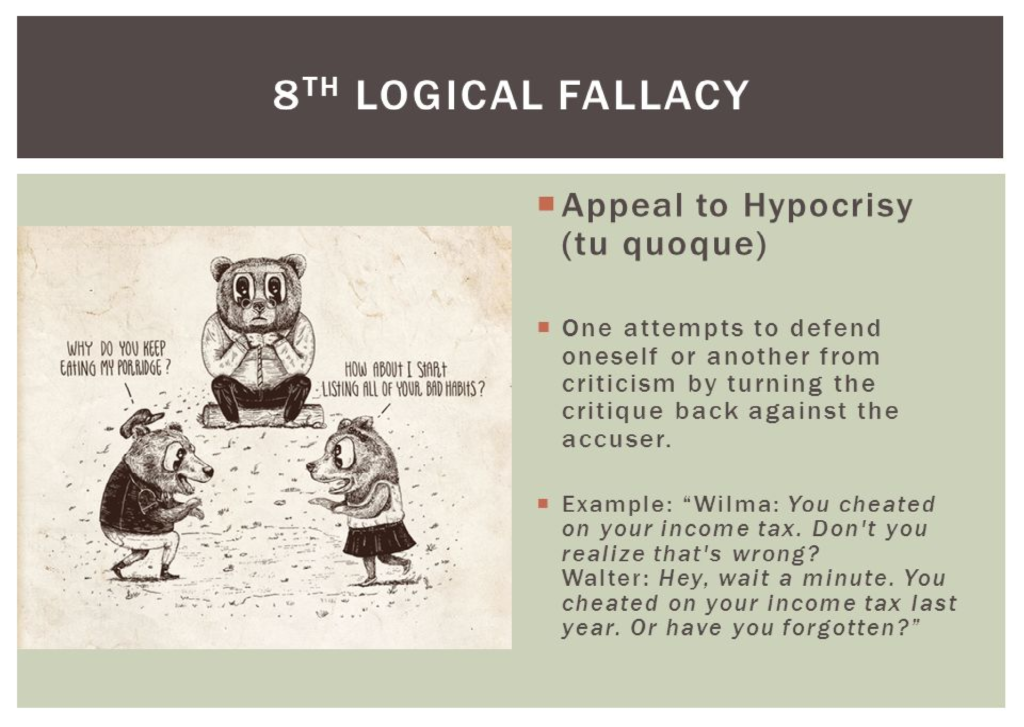

Tu Quoque/Appeal to hypocrisy

The “tu quoque,” Latin for “you too,” is also called the “appeal to hypocrisy” because it distracts from the argument by pointing out hypocrisy in the opponent. This tactic doesn’t solve the problem, or prove one’s point, because even hypocrites can tell the truth. Focusing on the other person’s hypocrisy is a diversionary tactic. In this way, using the tu quoque typically deflects criticism away from yourself by accusing the other person of the same problem or something comparable. If Jack says, “Maybe I committed a little adultery, but so did you Jason!” Jack is trying to diminish his responsibility or defend his actions by distributing blame to other people. But no one else’s guilt excuses his own guilt. No matter who else is guilty, Jack is still an adulterer.

The tu quoque fallacy is an attempt to divert blame, but it really only distracts from the initial problem. To be clear, however, it isn’t a fallacy to simply point out hypocrisy where it occurs. For example, Jack may say, “yes, I committed adultery. Jill committed adultery. Lots of us did, but I’m still responsible for my mistakes.” In this example, Jack isn’t defending himself or excusing his behavior. He’s admitting his part within a larger problem. The hypocrisy claim becomes a tu quoque fallacy only when the arguer uses some (apparent) hypocrisy to neutralize criticism and distract from the issue.

Hypocrisy Unveiled: Exploring Logical Fallacies and Navigating the Appeal to Hypocrisy

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies