Emotional Manipulation: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Analyzing the Appeal to Emotion. Free PowerPoint and Videos

Emotional Manipulation: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Analyzing the Appeal to Emotion

Emotional Manipulation: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Analyzing the Appeal to Emotion

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are like landmines; easy to overlook until you find them the hard way.

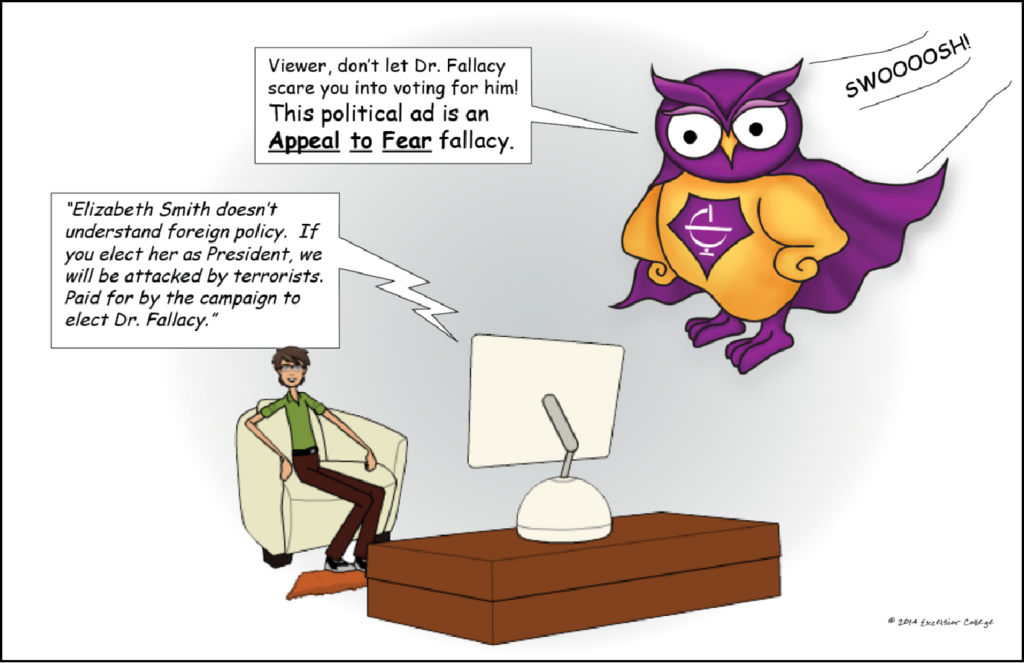

One of the most important components of learning in college is academic discourse, which requires argumentation and debate. Argumentation and debate inevitably lend themselves to flawed reasoning and rhetorical errors. Many of these errors are considered logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are commonplace in the classroom, in formal televised debates, and perhaps most rampantly, on any number of internet forums.

But what is a logical fallacy? And just as important, how can you avoid making logical fallacies yourself? Whether you’re in college, or preparing to go to college; whether you’re on campus or in an online bachelor’s degree program, it pays to know your logical fallacies. This article lays out some of the most common logical fallacies you might encounter, and that you should be aware of in your own discourse and debate.

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy

A breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy

Denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

The Appeal to Emotion

Argumentum ad misericordiam is Latin for “argument to compassion.” Like the ad hominem fallacy above, it is a fallacy of relevance. Personal attacks, and emotional appeals, aren’t strictly relevant to whether something is true or false. In this case, the fallacy appeals to the compassion and emotional sensitivity of others when these factors are not strictly relevant to the argument. Appeals to pity often appear as emotional manipulation.

“How can you eat that innocent little carrot? He was plucked from his home in the ground at a young age and violently skinned, chemically treated, and packaged, and shipped to your local grocer, and now you are going to eat him into oblivion when he did nothing to you. You really should reconsider what you put into your body.”

Obviously, this characterization of carrot-eating is plying the emotions by personifying a baby carrot like it’s a conscious animal, or, well, a baby. By the time the conclusion appears, it’s not well-supported. If you are to be logically persuaded to agree that “you should reconsider what you put into your body,” then it would have been better evidence to hear about unethical farming practices or unfair trading practices such as slave labor, toxic runoffs from fields, and so on.

Truth and falsity aren’t emotional categories, they are factual categories. They deal in what is and is not, regardless of how one feels about the matter. Another way to say it is that this fallacy happens when we mistake feelings for facts. Our feelings aren’t disciplined truth-detectors unless we’ve trained them that way. So, as a general rule, it’s problematic to treat emotions as if they were (by themselves) infallible proof that something is true or false. Children may be scared of the dark for fear there are monsters under their bed, but that’s hardly proof of monsters.

To be fair, emotions can sometimes be relevant. Often, the emotional aspect is a key insight into whether something is morally repugnant or praiseworthy, or whether a governmental policy will be winsome or repulsive. People’s feelings about something can be critically important data when planning a campaign, advertising a product, or rallying a group together for a charitable cause. It becomes a fallacious appeal to pity when the emotions are used in substitution for facts or as a distraction from the facts of the matter.

It’s not a fallacy for jewelry and car companies to appeal to your emotions to persuade you into purchasing their product. That’s an action, not a claim, so it can’t be true or false. It would however be a fallacy if they used emotional appeals to prove that you need this car, or that this diamond bracelet will reclaim your youth, beauty, and social status from the cold clammy clutches of Father Time. The fact of the matter is, you probably don’t need those things, and they won’t rescue your fleeting youth.

Emotional Manipulation: Unraveling Logical Fallacies and Analyzing the Appeal to Emotion

DOWNLOAD THE POWER POINT FOR FREE

Logical Fallacies

Also check out these free resources on Critical Thinking and Logical Fallacies